Language used by Academics with the Protection of Anonymity

Those in the political science discipline probably remember their first encounter with poliscijobrumors.com. For those outside, you have probably never heard of this particular message board, and you would have no reason to. As the URL suggests, the board specializes in rumor, gossip, back-bitting, mudslinging, and the occasional lucid thread on the political science discipline. By browsing the posts one can quickly see how the protection of anonymity results in the lowest-common denominator of discourse—even among members of the Ivory Tower!

If you are unconvinced, simply test Godwin's law for yourself.

The convergence of specific topics within a discipline and the promise of anonymity, however, makes for a very interesting data set on the use of language in this context.

I have always been curious what patterns could be extracted from the particular forum. Specifically, given the ability of people to mask their identities, which often leads to a very low-quality in discourse, is it still possible to identify topic areas of interest by examining the data in aggregate? Furthermore, will any of them have anything to do with political science?

The answer: kind of...

The message board has been around for a long time, so it was infeasible to go out and scrape the entire corpus. Short of that, I decided to create a text corpus of the first 1,018 threads in the General Job Market Discussion. The 1,018 comes from that fact that several threads include multiple pages, so rather than strictly stopping at 1,000 pages I decided to try to be inclusive of full threads.

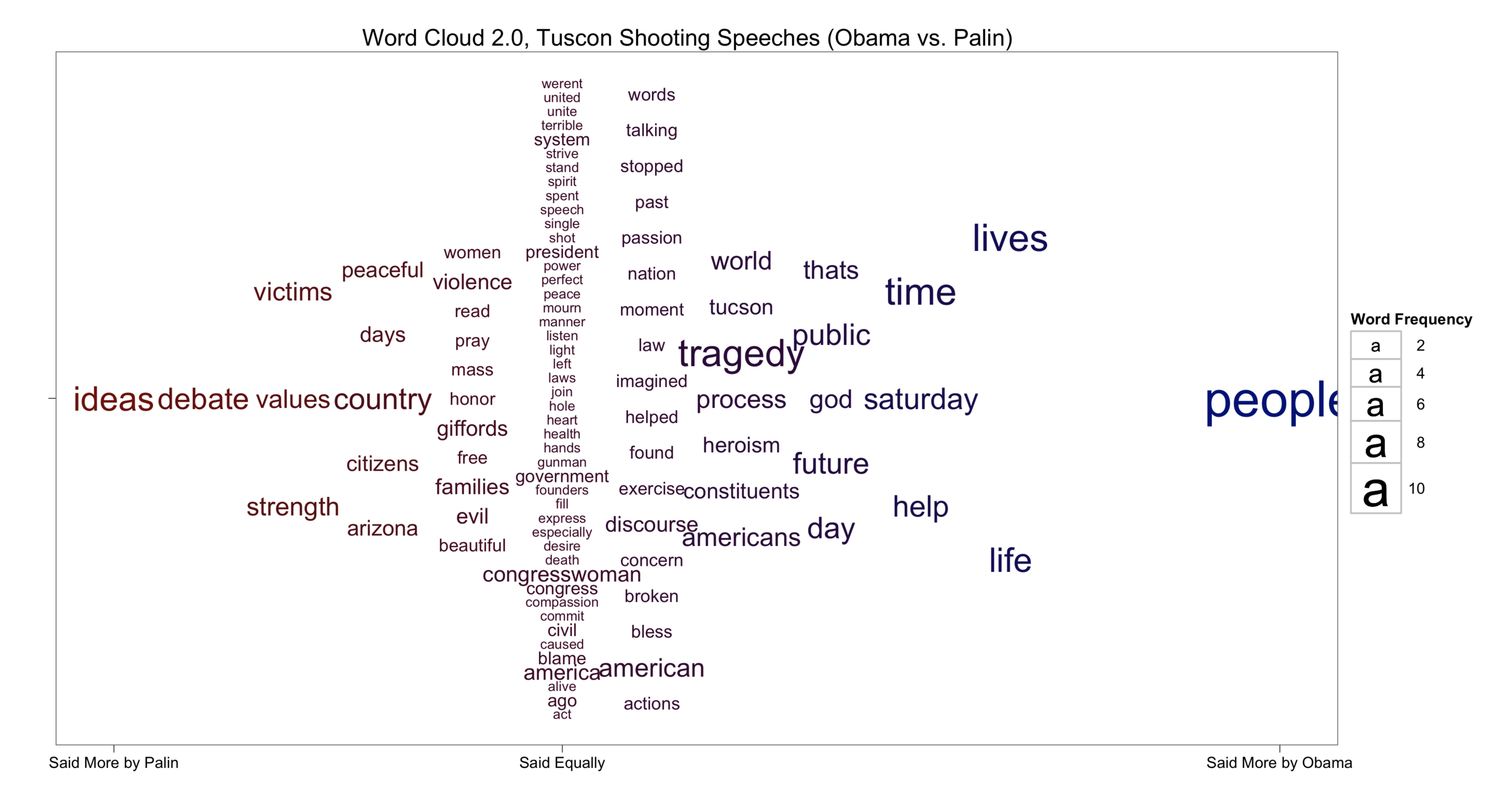

With all the data in hand, the analysis was very straightforward. I constructed a term-document matrix, with the usual linguistic noise removed, and performed a simple matrix multiplication to get the number of times each of the words were used in the same thread. The result is an N-by-N matrix, wherein the elements are the number of times a words were used in the same thread. We can think of this data as a weighting among words: the higher the number the "closer" the affiliation.

Another way to construct this is graphically, whereby the data is a weighted adjacency matrix. Then, the words become nodes and the edges are weighted by the co-occurence weighting in each element. This is helpful because we can now use force-directed methods to place words near each other in two-dimensional space. , both the x- and y-axis position of the word is directly relevant the how words relate to each other.

This positional data also gives us a sense of distance between words, i.e, the further apart words are the more unlikely it will be that they are used in the same thread. From this we can create "topic" clusters. That is, we can attempt to divide the words into clusters based on their distances, and these clusters can represent consistent topics within the entire corpus of data. To do this I use simply k-means clustering, and use 8 centers for the clusters. The choice of 8 was made because the "Dark2" Color Brewer palette only has 8 colors in it (art vs. science compromise).

Finally, because I think it is an immediately obvious way to convey this, words are sized by the log of their frequency in the entire corpus. The visualization above is the result of this analysis, which follows from previous thoughts on building better word clouds.

What can we say about this analysis? It seems—to me—that the topics are fairly similar. Moreover, despite the low-level of the overall discourse on the forum, in aggregate the topics are very relevant to the political science discipline and job market. That said, a non-negligible amount of profanity does make it into the visualization, though thankfully those words are not among the most frequently used. The placement of certain cities and universities into various topic clusters is also interesting.

Keep in mind that the method I use here is very different from the LDA topic modeling I have discussed in the past. Perhaps that would have produced better topic clusters, however, I do think one benefit of this method is the non-stochastic nature of the clusters.

Code available for download and inspection at the ZIA Code Repository.

R Packages Used

- XML

- tm

- igraph

- ggplot2